We had a lot of fun in class this past Friday.

Because it was Patron’s Day, we had a special schedule with 20 minute classes. Twenty minutes is too short for some lessons bu t perfect for practicing public speaking.

t perfect for practicing public speaking.

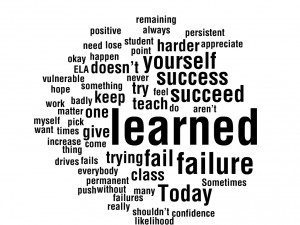

To be honest, I always considered myself a writing teacher. Even though I require presentations as part of every class I teach, I never stopped to consider what I should do to prepare the students except to remind them to speak loudly and clearly and make eye contact with the audience.

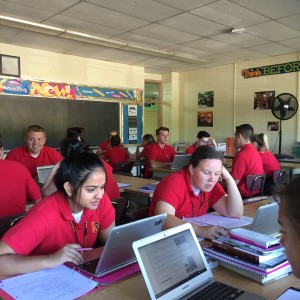

Several years ago, I visited the Science Learning Academy with my principal to investigate the way Chromebooks were being used in the classes there. I learned a great deal about Chromebook classrooms that day, but I learned even more about students and public speaking.

When we created the Digital Literacy course, a project based course, we began to look at the ways that students should deliver their presentations. My colleagues and I were all too familiar with students reading slides, and since we were creating a course that would require presentations, we started to consider how to help our students do a better job with public speaking, specifically with presenting information orally to a class.

These ideas and others are now part of what I teach to all of my students. And what I love is that I start making visible the kinds of things that good speakers do by having some fun with Tongue Twisters, something I learned from my PLN coach Bernadette Janis.

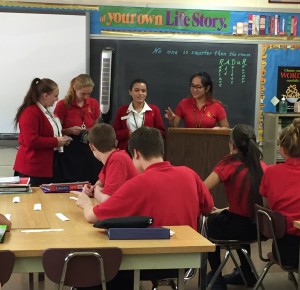

Each group is assigned a particular Tongue Twister, and each student in that group gets a slip with th e words. The directions are simple. Students are directed to practice together and decide the best way to present the Tongue Twister multiple times. I usually say they need to say the Tongue Twister one time more than the number of people in their group. I invite them to consider ways to make this work. Each student could say it once and then the whole group one time together. The entire group could recite it together the requisite number of times. Or they could come up with any way that works for their group.

e words. The directions are simple. Students are directed to practice together and decide the best way to present the Tongue Twister multiple times. I usually say they need to say the Tongue Twister one time more than the number of people in their group. I invite them to consider ways to make this work. Each student could say it once and then the whole group one time together. The entire group could recite it together the requisite number of times. Or they could come up with any way that works for their group.

Over the past few years I have been doing this, there have been groups with students that have difficulty with speaking. Students with speech issues and international students are not able to say the sentence alone, but when they are part of a choral group, they can dip in and out of saying the Tongue Twister and actually practice fluency as part of the exercise.

On a whole, the kids laugh a great deal. And the rule is if anyone makes a mistake, the whole group starts over from the beginning. Sometimes they laugh so hard, they have to restart four or five times.

I find myself smiling. I smile because I watch the student whose parent told me that she has a great fear of public speaking as she stands in front of her peers laughing and trying to say some silly words. I smile because the groups that have students who cannot speak fluently take care of their teammates. They find ways to support each other. I smile because they are practicing speaking in front of the class in a non-threatening and supported way.

Of course, we have many more aspects of public speaking to cover. I will model for them. I will find ways to support them, reviewing key points like enunciation, projection, eye contact, extemporaneous speaking. But I am so happy that the first time my students stood in front of the class they were laughing and having fun.

Hopefully, they will feel like Brittany, a former Digital Literacy student, who in a recent article in the student online newspaper said that not only did she learn tech skills in that class, but that she “was able to become more comfortable speaking in front of people from this course.”

Out of the mouths of teenagers.